Category

- Concrete Best Practices

Following our recent blog post Durability Testing 101: The Permeability Test, which highlighted how permeability affects concrete durability, we now turn our attention to another critical testing method: absorption testing, sometimes known as sorptivity testing.

This approach offers additional insights into concrete’s watertightness, a key factor in its overall durability. It is of particular concern in applications where concrete will be exposed to aggressive environments and specifically, to chloride and sulphate ions.

In this post, we will explore what absorption testing is, examine its limitations, and discuss how Kryton’s Krystol Internal Membrane (KIM) product line addresses absorption challenges.

What is Absorption Testing?

Absorption testing measures the amount of water that penetrates concrete samples through capillary suction when the concrete is submerged. A lower absorption rate indicates better watertightness, which is crucial for the longevity and reliability of concrete structures exposed to moisture and water.

Absorption testing is outlined under the standards:

- BS 1881-122: 2011: Testing Concrete: Method for Determination of Water Absorption

- ASTM C 1585: Standard Test Method for Measurement of Rate of Absorption of Water by Hydraulic-Cement Concretes

How Absorption Testing is Conducted

The absorption testing process involves several steps:

- Sample preparation: Concrete cylinders are cast and moist-cured for a standard period of 28 days, or as specified by the project requirements, to allow for hydration and strength development.

- Slicing: A 2-inch (50-mm) slice is cut from the cured cylinder and placed in a controlled environment (122°F or (50 °C) and 80% humidity) for three days to stabilize its moisture content.

- Sealing and Submersion: The slice is coated with epoxy on its outer surfaces to prevent side and top absorption, sealed in a container for 15 days to reach moisture equilibrium, and then submerged in water.

- Measurement: The change in mass due to water absorption is measured over time, with smaller mass changes indicating better water resistance and higher concrete durability.

This testing method provides initial quantitative measures of concrete’s ability to resist water ingress, though it has some limitations.

Limitations of Traditional Absorption Testing

While absorption testing is invaluable, it comes with inherent limitations:

- Reactivity Oversight: It fails to account for reactive processes that may affect water absorption, like Krystol Internal Membrane (KIM).

- Assumption Errors: There is an assumption that all weight gain in the concrete sample is due to water absorption.

- Temporal Limitations: The duration of submersion is typically short, which may not accurately simulate long-term environmental conditions.

These limitations can skew results, especially in concretes that include specific types of admixtures.

How KIM Effects Absorption

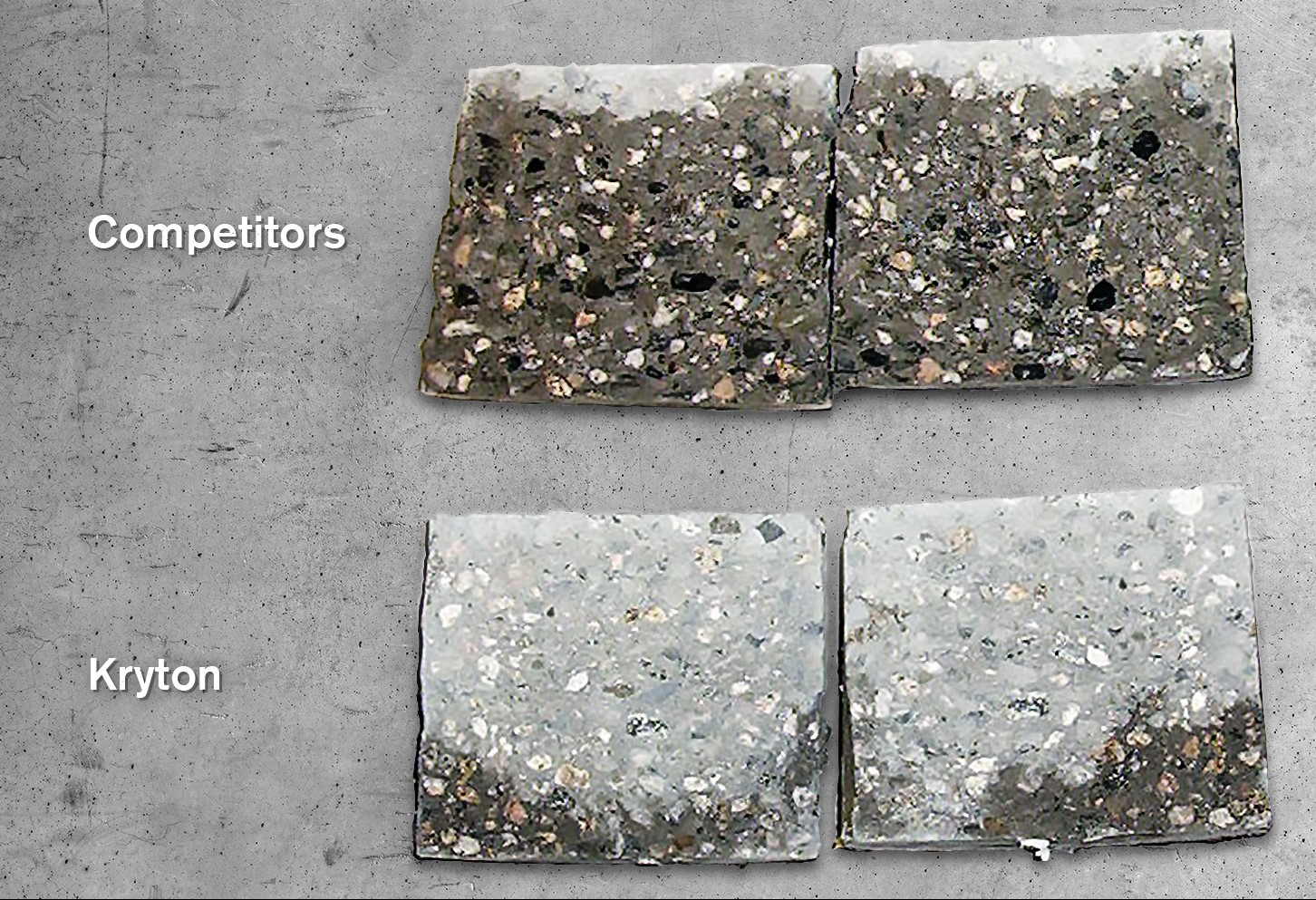

Kryton’s Krystol Internal Membrane (KIM) is a hydrophilic crystalline waterproofing admixture that significantly enhances concrete’s water resistance. Upon contact with water, KIM reacts with unhydrated cement particles to form insoluble crystalline structures that fill capillary pores and microcracks, effectively blocking water ingress.

In absorption testing, the unique properties of KIM-treated concrete may initially not be fully apparent, especially in early curing stages. However, as the concrete continues to cure and becomes more saturated, these crystalline structures mature and strengthen, enhancing the concrete’s watertightness over time.

To accurately capture this progressive improvement, it is recommended to perform absorption tests at later stages (56 or 90 days) rather than the conventional 28 days. Longer curing periods before testing can provide a more accurate depiction of the concrete’s watertightness.

Complementary Durability Testing

By understanding the nuances of absorption testing while using innovative solutions like KIM, we can significantly improve our assessment of concrete durability.

Additional testing, such as the Permeability Test and the Rapid Chloride Permeability Test, can offer a broader view of the concrete’s resistance to water and chemical ingress.