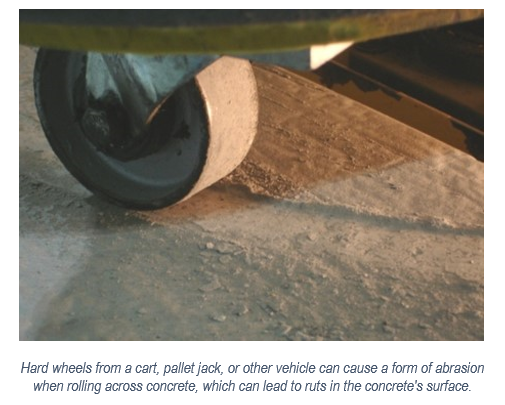

When it comes to getting a durable concrete slab, a critical part of it involves keeping the concrete resistant to abrasion. Without that resistance, construction professionals will often encounter ruts, dips, potholes, or worse in the surface of their concrete. All of which can lead to safety hazards and operational inefficiencies.

Professionals usually try to counter this with conventional surface-applied concrete hardening solutions. But these aren’t reliably effective and come with a number of setbacks.

To look into why that is, we’ve decided to explore the bad, the good, and the better parts about concrete abrasion resistance. Helping us in this discovery are two of our Smart Concrete® experts: Jeff Bowman, one of our technical directors, and John Andersen, our territory manager for Western Canada. To start, let’s dive into some of the negative aspects surrounding concrete abrasion resistance.

Thank you for joining us on the first part of this interview series. Let’s start by discussing what abrasion actually is and why it is an issue for concrete in the first place.

Jeff: Abrasion describes the steady loss of material from the concrete through some sort of mechanical action. It’s generally more of a surface phenomenon.

And this may also be combined with foreign particles trapped between those two phases that are also gouging and sliding through the concrete.

John: When we talk about the significance of that wear and tear on concrete, we typically think about just the cost of taking the building out of service and replacing the concrete. But there’s also a cost regarding safety. And it’s not just about the people tripping and falling and encountering all other hazards because of it. There’s also an issue of breathing in the concrete dust, the cost associated with keeping the facility and machinery clean, the cost to the equipment, and the reduced productivity due to the worn out concrete.

How exactly do construction professionals usually try to resolve this issue?

Jeff: Dry shake hardeners are quite a common product for this. I’m sure many people reading this now probably use or specify them.

But for anybody who’s not familiar with them, a dry shake hardener is some sort of blend of cement and possibly some other additives and an abrasion-resistant aggregate particle, such as aluminum oxide (also called emery). And these products get broadcast in a dry form overtop fresh concrete and then worked into the surface during the final finish.

Now, certainly, these products can work and can give you a good abrasion-resistant finish if they’re installed well. The challenge that the industry has is they’re very difficult to install.

Dry shake hardeners are applied in two portions, and there’s some work that needs to be done in-between. And one of the significant challenges of this application is that it all takes place in a very time-critical period. All the steps are time-critical, and it can be very easy to miss that perfect window of opportunity.

There are just so many variables that could be happening with the concrete and with the weather. And if workers start to have trouble with it, sometimes they just can’t get a full specified amount of the dry shake applied to the concrete.

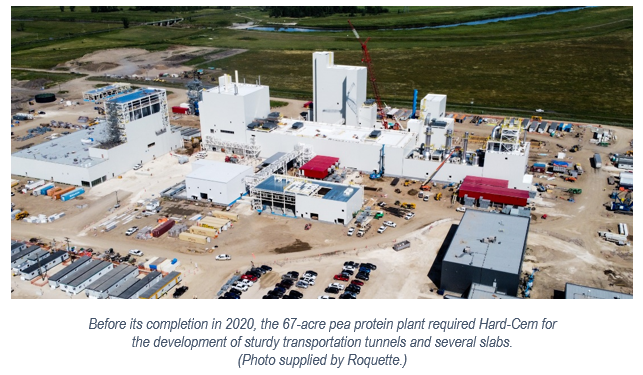

John: That’s exactly the challenge that the contractor Graham Construction faced when they were building a new pea protein plant in Manitoba. This is a massive facility with large slab pours, and they were trying to get that shake-on hardener down in that little window of opportunity. And they lost the first slab.

They eventually changed to Hard-Cem to get away from the challenge of that little window of opportunity for properly applying the shake-on.

Are there other challenges that come with using dry shake hardeners?

Jeff: Another challenge that we see is that this work normally comes up fairly late in the day when workers have been at it for many hours and they’re just getting fatigued. This is a lot to put on them at the end of the day.

We also see that the dry shakes are very sensitive to bleed water. If there’s too much bleed water coming out when you apply the dry shake and you work that water back in, the surface will become weaker and is likely to delaminate. If you have a low-bleeding concrete, perhaps something with a lot of fly ash, there’s just not enough water there to really work it in properly. The concrete sets up too quickly.

There can also be challenges with wind. And of course, it’s very important not to use dry shakes with air-entrained concrete because the power troweling needed to really work them in properly leaves a high risk of delaminating the concrete surface. So there are many challenges to dry shake products that people might face.

There are also some products that professionals apply post-construction, right? What about those?

John: Yes, I think if you’re in Western Canada, where I live, many of these products use silicate as the base for their formulas.

Jeff: Right. When we’re describing liquid hardeners (which are sometimes called liquid densifiers), these are all some sort of silicate-based product. They work by penetrating into the concrete and reacting with the calcium hydroxide there, which is a by-product of cement hydration. That reaction turns into what is called calcium silicate hydrate gel, which is the normal hydration product of cement. It’s what gives the cement paste its strength and what gives concrete its properties. So this reaction pathway is really quite similar to the reactions you get from fly ash or slag or other supplementary cementitious materials.

That introduces some challenges in and of itself. Some suppliers of these products recommend limiting the amount of fly ash or slag you’re using in your concrete. That’s not always possible or desirable for many other reasons. Or they may recommend delaying the application for at least 28 days to allow the concrete to come up to its specified strength first so that the silicate is not competing with the other cementing materials.

Does their application work effectively?

Jeff: While they are often used or specified specifically to increase the abrasion resistance of the concrete as placed, that’s not really what they’re intended to do.

Now, liquid hardeners do serve an important purpose. If a contractor does have a slab that has had some challenges when they’re placing it, the surface might be poorly hydrated or weak or might have dried out too early. These products can help strengthen that surface as a remediation measure.

But they’re not really an appropriate material to specify as an abrasion-resistant material for concrete that’s been otherwise properly placed and finished.

Are there other solutions that have been used to increase concrete abrasion resistance?

Jeff: Another common solution is high-strength concrete.

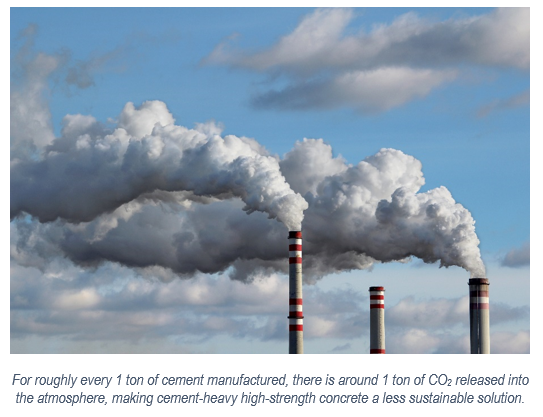

And why not just use stronger concrete? You get better abrasion resistance. And normally, this approach would be just using a mix that has more cement. You could use more fly ash or slag or maybe silica fume to really get that strength up and keep that water-cement ratio down real low. The concrete gets stronger, and the abrasion resistance is better. And this generally does work.

But there are some limitations.

But there can also be some consequences. Any time you are using a stronger mix, especially with anything that has more cement paste, you’re getting more hydration. That generates more heat in your concrete.

More paste means more shrinkage. More shrinkage normally means more cracking. And if you’re pouring a slab, you also now get more curling, so your floors just don’t stay as flat. And curling can result in a lot of damage and wear at the joints.

All of these things are actually really bad. They target some of the core properties that a facility owner expects of their floor. An owner wants more than just good abrasion resistance. They want their floor to perform in many other ways.

And as an added bonus, using high-paste strong mixes comes with a cost premium. Because you are using so much more cement in the concrete, the carbon footprint of that concrete can go up quite significantly.

So most popular concrete abrasion-increasing efforts don’t seem to work as well as expected. Is there a better way to get that abrasion resistance?

John: Adding Hard-Cem into concrete at the batch plant! Hard-Cem lives in that concrete paste, and that’s how it works. It increases the resistance to abrasion and erosion that way. It’s easy to apply. There are no negative effects on your plastic or your hardened concrete. It’s fully compatible and used often with air-entrained concrete, so no longer do you have to specify products like this just for indoor use. You can now use it outdoors. And it can be used in horizontal and vertical slabs, behind formwork, in precast, and in shotcrete. There’s a huge opportunity for this product to be used often in mining applications as well.

And Jeff very clearly articulated the difficulty in applying the shake-on hardeners. So no longer do the jobsites have to take all this into consideration. Basically, they can just order Hard-Cem when they order their concrete. And there’s no harmful dust exposure.

Hard-Cem’s been used for 18 years now for over 7 million m2 (80 million ft2) in all kinds of applications. And many of the top-producing concrete companies have branded their own durability concrete using the Hard-Cem admixture.

Once concrete finishers get to use this, they start to ask for it by name because it just makes their job that much easier.